On April 13th, 1994, one of the best (if not the best) and most critically acclaimed rap albums ever recorded was released, Illmatic. It was released by one of the (if not the) best Rap lyricists of all time, Nasir bin Olu Dara Jones, better known as the rapper Nas. The album is widely hailed in Hip-Hop circles as a classic that altered the landscape of Hip-Hop. One could argue that it was influenced by almost every Rap album that came before it, and it influenced almost every Rap album that succeeded it; but to me, it’s become more than that. To me, it’s more than great music; Illmatic is a work of art. It’s a coming-of-age story and street tale that can be viewed in the same light as some of the greatest literary and cinematic works we’ve known, recognized and appreciated in modern times.

Fans and those who’ve followed Nas’s career know him as a son of Queens, but he was born in Brooklyn on September 14, 1973; the same year credited as the birth year of Hip-Hop. He was born to Fannie Ann Little, a postal worker, and Olu Dara (born Charles Jones III), a Jazz musician. Nas growing up in parallel with Rap and the Hip-Hop culture, and his experiences as a child raised in the Queensbridge Houses; the largest housing project on the continent, fostered a love for the music and level of creativity and imagination that would bring to being his ability to stand out as an all-time great talent amongst his cohorts. As a youth, Nas studied Hip-Hop and other forms of music, art and literary works, and the immediate surroundings that engulfed him in Queensbridge to begin crafting the profound concepts, stories and lyrics that would later lead to him being labeled a phenomenon by fans and critics.

By 1991, these unique talents were on full display when Nas guest starred on a song with Main Source, a rap collective from Queens. The posse cut was called Live at the Barbeque, and though he was still only seventeen years old at the time, Nas’s debut verse stood out amongst his more experienced peers. Nas’s verse wasn’t only outstanding compared to who he rapped next to on the song, however, other rappers who heard his verse also took notice. The verse made Nas a sought-after commodity in the industry; and via a subsequent feature on a Live at the Barbeque spin-off track in ‘92, another posse cut called Back to the Grill, Nas continued to impress. Back to the Grill was a song by MC Serch, from the group 3rd Bass, who would also manage Nas and help him secure his first deal with Columbia Records. Later that same year, Nas’s debut single, Halftime was released on MC Serch’s soundtrack for the movie Zebrahead. His performance on the song did not lessen the anticipation for more Nasty Nas, and contributed to what was a growing expectation for him to deliver greatness on his prospective debut album. To heighten those sentiments, the project wouldn’t be released for almost another two years after the release of Halftime.

Halftime was actually the first time Nas grabbed my attention. Though it happened in passing, I still recall the moment like it was yesterday. I was at my uncle’s house in Hampton, Virginia. I was 12 years old and had been outside in his backyard hanging out with my cousins from down there. For whatever reason, I went into the house to do something inside, and when I opened the back door to come in, the video for Halftime just happened to be on the TV that I was passing. I didn’t know who Nas was at the time, so I didn’t stop, but as I was passing by, I noticed that even against the hard driving beat that he was rapping over, Nas’s voice and delivery cut through the sonics like a blade. Though I didn’t stop to check, I remember thinking, who is that dude?

In the almost two-year period between Halftime and the release of Illmatic, the buzz around Nas died down a bit; especially outside of the New York area. Very few knew that during that time, he and a host of top-notch New York beat makers and producers were coming together to try to make a classic. Nas’s promise made the legendary beat maker and producer DJ Premier from the also legendary group Gang Starr want to be a part of the project. Also from Queens, the legendary rapper and producer Q-Tip, from one of the top groups ever in Hip-Hop, A Tribe Called Quest, believed that Nas was a phenomenal talent and contributed his production and vocal talents to the album. Pete Rock, another legendary beat maker and producer, at that time best known for being in the rap duo Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth and his work with his cousin Heavy D. also came through to deliver production and vocals for Nas’s debut effort. Large Professor of Main Source, the group that gave Nas his debut verse, not only rapped alongside Nas on Live at the Barbeque to help launch the phenom’s career, but also joined his Queens counterpart to help solidify the production on his first project. Nas’s childhood friend from Queensbridge, L.E.S. rounded out the team of producers that shaped the aesthetic for Illmatic. L.E.S. was the least known of the production team at the time, but his contribution would fall right in quality-wise with the rest of the A-listers Nas recruited to create the album’s stand-out soundscape. Nas had a vision for what he wanted his first album to sound like, and he had a cream-of-the-crop team to help him bring that vision to life.

By the end of ‘93, the album was done. A masterpiece had been crafted by a team of savants and a phenom, now it was time to exhibit this piece of art to the world. On January 13, 1994, the single that would lead the album’s launch was released; the track was called It Ain’t Hard to Tell, and just as the title suggests, Nas’s extraordinary lyrical ability was very evident.

In the first line of the third verse, Nas announces the song as a “rythm-atic explosion;” an appropriate descriptor for how the combination of beat and lyrics appeal to the listener’s ears. The song features four samples on the beat infused into one by Large Professor, but the prevalent drivers of the sound are the deep and rolling baseline, and in the wordless chorus, the piercing jazz horns, and the sample from the Michael Jackson song, Human Nature, which echoes throughout the hook; or the space where most Rap songs feature catchy choruses. Hooks had become a big part of marketing Hip-Hop music to larger audiences at that time, but It Ain’t Hard to Tell instead transitioned into those parts of the track with pronounced pick-ups in sample sounds that refrain throughout in place of memorable word refrains that were, and still are, the more common practice.

Nas’s unique lyrical delivery fits perfectly with the cadence of the beat, yet and still, his unmistakable voice stands out over the busy and rich production by Large Professor, making it almost impossible to ignore how gifted he is with wordplay and phrasing. His extraordinary ability is also exactly what the song is about. Up to this point, each of Nas’s songs and verses that we’d heard had focused on this very topic; his phenomenal rapping capability. Through his words, he’d cast himself as a phenomenal specimen that had before been unseen or heard. Nas had successfully figured out a plethora of ways to make these statements of his grand prowess; and while his words expressed the sentiment, the verses he delivered simultaneously verified the claim. In this regard, he appeared to be the second coming of the great Rakim, who’d clearly influenced his style of flow. Like Rakim, Nas mythologized his rapping ability, but naturally, he took it a step further in rhetoric. The track is laced with references to having effects on his listeners and objects which are mostly humanly and earthly impossible. Nas is an other-worldly superhuman on the mic by virtue of his claims, but because he actually is so good, he makes claims like the one of him being “half man, half amazing” seem somewhat more palpable; and as the listener, you actually welcome and want more of the braggadocio.

Like Rakim, Nas utilized a monotone, yet somehow charismatic, conversation style flow that sounded like he was effortlessly piecing words together as if they were being perfectly fitted into a puzzle. Aside from taking the braggadocious rhetoric to another level, however, Nas also had a rarely utilized way of delivering his lines for that time. Most rappers utilized either the drum or snare patterns in a beat, or both, to ensure that they’re rapping “on beat,” or to create a comfortable “pocket” or cadence to ensure the words don’t sound out of place or awkward over the beat. Nas’s bars often spilled into one another, and his flow was focused less on cadence and more so on the way the words flowed and sounded together. Nas sort of created his own pocket with the words instead of letting the beat lead his delivery as much as other rappers may have, but the words are so profoundly fitted together, and delivered so smoothly and effortlessly that it doesn’t detract from the greatness or quality of the product. One could argue that his run-on style delivery only added a unique quality to his artistry in a time when uniqueness was necessary.

I can remember the first time I heard It Ain’t Hard to Tell when I was thirteen years old. My cousin and I were watching TV, and I turned the channel to Rap City and the video was on. My cousin excitedly said, “Oh, he’s supposed to be good.” I have no idea how he’d heard that. We talked about music a lot and this guy was never mentioned, but I excitedly replied “yeah,” as if I’d known. We moved on to another topic before the video was over, and I’d never heard what my cousin had heard, but while watching the video I thought back to two years prior when I was at my uncle’s and said to myself, I think this is the guy I remember seeing down in Hampton. Sure enough, it was. I had now put a name with the face and voice, and from that point forward, Nas as an entity was on my radar, and would forever be an artist whom I would endearingly follow.

In many ways, Halftime and It Ain’t Hard to Tell were ideal lead singles for the album. On both, Nas’s densely rich and deliberate style was on full display, and he’d proven that he could deliver multiple verses on a song as effectively as he’d delivered single verses as a stand-out in his previous features. The two songs as stand-alones, however, didn’t convey how each track on the album went together like perfectly blended ingredients, or a masterfully crafted painting; but in a little over four months, the Hip-Hop world would soon begin to discover.

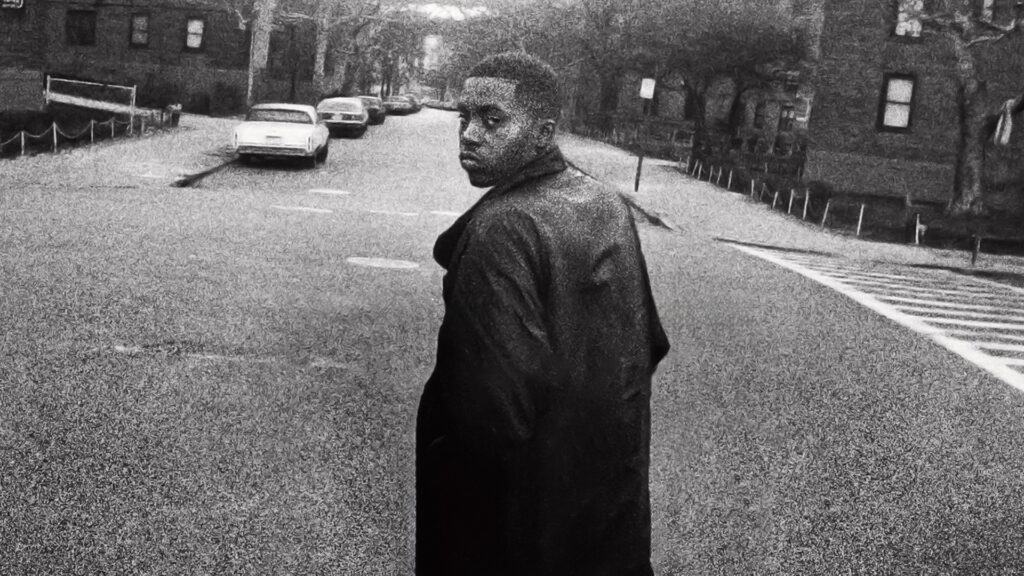

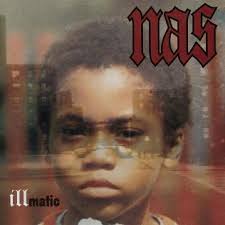

The greatness of Illmatic would begin at the album cover. The album art is now iconic. The slightly transparent picture of Nas circa the ages of seven to nine, with the Queensbridge Houses in the background says so much about the album and Nas himself. The introspection that characterizes Nas is depicted. The idea that you’re about to hear an artist’s account of their life from childhood to adulthood is captured. The imagery is also representative of the fact that Nas and this album are both so New York City, and so Queens and Queensbridge centric.

Just viewing the cover as art; especially now knowing the content of the album, there’s also something being stated in Nas’s stoic face posture in the image. You get the sense that this kid is somewhat sad and pensive, but at the same time, he’s perfectly okay to navigate the tough terrain in which he dwells; the very projects depicted behind him. It’s almost as if that kid is telling you that he’s been through and seen a lot, but that he’s doing just fine. He’s taking it all in and learning along the way; and what you’re about to hear is the product that was produced, from his perspective. I think there’s something else also being represented in this art. It may’ve been unintentional; maybe I’m looking and thinking too deeply, but it feels intentional that Nas’s face is positioned out in front of Queensbridge. Nas, most would say, has been the face of Queensbridge since Illmatic dropped. It’s no wonder this album cover is as iconic as it’s become. The fact that the music is actually great doesn’t hurt, but in so many ways, Nas and his team couldn’t have picked better art to represent this album and to introduce him as an artist to the world. With this album, however, this is only the beginning of the greatness of the artistry.

The intro to Illmatic, titled The Genesis, is almost as classic as any of the tracks, and many consider the actual songs on this album to be a collection of classics. The first sounds you hear on the album are the sound of a train speeding along tracks, replicating the sound of the New York City subway and El trains navigating the city. The sound not only serves as an announcement that this album will encapsulate the sounds of the city, but also metaphorically escorts the listener into the city; into Queensbridge, and into Nas’s mind and world.

Once the listener arrives and the train moves along out of earshot, the intro transitions into another assembly of defining metaphors for the album. A dialogue begins between what the listener can assume is an older man speaking to a boy or younger man. The dialogue is sampled from the movie Wild Style, Hip-Hop’s first major movie, released in 1983. It serves as a symbol for where Nas was coming from, the essence of Hip-Hop; the “old school.” The dialogue also touches on one of the themes from the album; coming of age. The elder person in the dialogue is chastising the younger about their lack of motivation; for sitting around doing “this,” which is assumedly some form of Hip-Hop. Simultaneously, and almost inaudibly, in the background is Nas’s Live at the Barbeque verse playing. A pattern that Nas would utilize throughout his career; hearkening back to his great past works in the current, signifying his then-to-now journey, while simultaneously showing off his prolific ability. In the dialogue, the listener can imagine Nas in the position of the younger of the two, and when the older says to the younger, “Stop f—–g around and be a man. There ain’t nothin’ out here for you,” you get the sense as the listener that metaphorically Nas is replying when the younger of the two says, “Oh yes there is…this;” and that “this” is Hip-Hop.

The Genesis then goes on to further embody the essence of the album with a blend of the old and the new as the beat that plays is also from Wild Style, Grand Wizard Theodore’s Subway Theme. The oratory that then begins is unmistakably more current for the time, however. Nas and his crew start talking about how there were a lot of rappers out at the time doing Hip-Hop inauthentically. A scene is set of them all in one room, counting money, conversing, drinking, smoking; engaging in the typical things city youngsters would engage in, one could imagine. The words and slang they used epitomized early Nineties New York, and via their criticisms of other contemporary artists, they announced that this album would be different from that. This album would be pure Hip-Hop, divorced from the commercial tropes and themes that were becoming prevalent at the time. This album, in the dopest way, would capture and represent the glories and realities of Hip-Hop culture of the streets; where and what people were actually living. This album would be the ultimate encapsulation of that, and at the same time, this album would be beyond the illest thing you’d ever heard. This album would be “Illmatic.”

Leave a Reply